“I’d seldom use the word “fun” to describe the music of the ultra-serious Brahms, but it was just that to see and hear this superstar duo (Zukerman and Forsyth) go at it in their virtuoso solo passages.

Right from the start of SOTA’s rendition, cellist Forsyth asserted her stringent, incisive tone into the equation with a cadenza that caught the ear and kept the listener rapt until the woodwinds entered with their brief, soothing sonorities. Zukerman’s cadenza, in turn, was exquisitely sweet-toned, and when the two soloists played together in double stops, the effect approached the amplitude of a string quartet. No less exhilarating was the ability of these two to sound like a single instrument in passagework that traversed the gamut and made it hard to tell where one instrument left off and the other took over...””

“I was a big opera buff when I was growing up. I had a huge music collection and it was mostly all opera; I loved the stories and the dramatic arias, which I used to practise on the cello. For me it was all about the sentimentality, and I also loved Romantic works for the same reason. I was eleven years old when I first heard Strauss’s Don Quixote: Pierre Fournier was performing with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra and I fell in love with it. When I started learning it myself, it became the piece that helped me understand it was OK to be emotional about instrumental music. Before that, I was simply improving my technique – I even felt embarrassed about my emotions while I was playing! I lived more through vocal pieces than anything instrumental, and when I had a choice I’d always go for the more vocal-sounding work. Even now, I get goosebumps when I’m playing Don Quixote live on stage, and I have to tell myself, ‘Focus! Focus!’ as if it’s wrong.”

'“Forsyth’s performance was comparable, drawing a lush, hall-filling sound from her Testore cello. Offenbach, a cellist himself, wrote skillfully for the instrument, with a surefooted sense of line and a deep understanding of technique. Forsyth made the most of the possibilities of the piece, with thoughtful phrasing, flawless intonation, and a just-right vibrato that coalesced into a moving, musical whole…

Guest conductor Asher Fisch, who led the BSO on Saturday evening, has long been a champion of Dorman’s work. This busy and ultimately conservative Double Concerto was a star vehicle for its soloists: the married duo of violinist Pinchas Zukerman and cellist Amanda Forsyth, longtime partners in both performance and life. With her robust timbre and earthy accents set against his silvery sound, which was ethereal without being silky, they played with obvious relish, and sounded more at ease with the piece than the orchestra did. After intermission, Zukerman again joined the BSO for Beethoven’s stately Romance No. 1 in G, dispatching tart and tight phrases with a few sour notes.

BOSTON — For renowned violinist Pinchas Zukerman’s 70th birthday, the world has been gifted a new piece of music.

“The Double Concerto for Violin and Cello and Orchestra,” composed by fellow Israeli Avner Dorman, will have its US debut on Saturday, August 3, at Tanglewood. It will be performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) under the baton of Israeli conductor Asher Fisch.

Lenox — Violinist and conductor Pinchas Zukerman‘s relationship with the Boston Symphony Orchestra began in 1969 at Tanglewood with a performance of Tchaikovsky’s Concerto for Violin in D Major. On Saturday, Aug. 3, he will make his 23rd Tanglewood appearance, joined by his wife, cellist Amanda Forsyth, performing, for starters, Beethoven’s Romance No. 1 in G for violin and orchestra. But the weightiest event of Saturday’s concert is the American premiere of Avner Dorman‘s Double Concerto for violin, cello and orchestra.

Very different fare arrived with the world premiere of Avner Dorman’s “Double Concerto”, in which the temperaments of solo violin and cello were deliberately pitted against and then harmonised with the rest of the orchestra. Benjamin Northey steered brilliant performances by Zukerman on violin and Amanda Forsyth on cello. For the record, Zukerman was all in black and Forsyth in a fiery Chinese red dress, a contrast that added a bit more theatre to moments when their instruments spoke quite differently with each other and the orchestra.

Pinchas Zukerman on violin and Amanda Forsyth on cello know each other very well on a range of levels, and their understanding of what makes each other ‘tick’ was especially evident in tonight’s incisive performance. It was a delight to see their superlative musicianship in action, both separately and as a partnership. They fed off each other and the whole was greater than the sum of their individual parts. Dorman was sitting in the audience and his appreciation of Zukerman and Forsyth’s musicality was abundantly clear. Although Dorman knows his own score inside out, he surely would have gained deeper insights into his own creation because of the adeptness and acuity of Zukerman and Forsyth’s performance.

Cellist Amanda Forsyth joined Zukerman in a very fine reading of the Double Concerto. Even more than her partner, Ms. Forsyth displayed a marvelous air of spontaneity, seeming to inhabit the music as she played it. Together, they put their considerable chamber-music experience to great use in Brahms’ final orchestral work. The playing showed a wide range of color, not only from the two soloists, but also from the orchestra.

As far as the concertos were concerned, Mehta proved a mensch, putting his soloists first. Violinist Pinchas Zukerman was slow to warm up Thursday in the Violin Concerto, with nuance coming more easily than tone quality. He was joined by the impressive cellist Amanda Forsyth on Saturday for a dramatic reading of the Double Concerto, which proceeded the Fourth Symphony.

The three Concertos, conducted from memory, are a bag of mixed chemistries. Zuckerman's autumnal Beethoven does everything right, yet in its meditation and carefulness loses energy, sounding more held back than others sharing its (relatively quick) forty-five-minute span. The fire burns low. In the Brahms Double (playing from music) he's joined by his South African-born Canadian wife Amanda Forsyth, a latter-day protégé of William Pleeth. Musically (and visually) it's an oddly old-fashioned encounter, neither protagonist entirely comfortable with each other or the nature of Brahms's duo writing, Mehta driving a forceful, even belligerent, account in between.

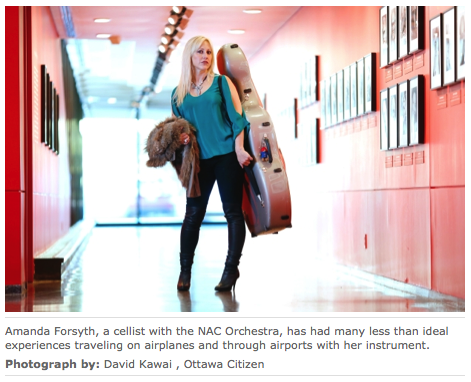

Amanda Forsyth has been travelling the world since she left the principal cello chair with the National Arts Centre Orchestra some three years ago.

From Seoul to Sydney; St. Petersburg to Sao Paolo, she’s lugged her cello Carlo to concert halls across the globe as a soloist or as a member of the Zukerman Trio with her partner Pinchas Zukerman and pianist Angela Cheng.

Now she’s about to step back on the Southam Hall stage as a soloist for the first time since she left to pursue a career in the wider world.

She will perform a concerto written for her by the Canadian composer Marjan Mozetich, who has more than 70 works to his credit and has won several major awards including the 2010 JUNO for Best Classical Composition of the Year.

It is rare to have a full concert of string sextets, and it is rare indeed to find playing as beautiful as that provided by the Jerusalem Quartet and their two exalted collaborators, violist Pinchas Zukerman and cellist Amanda Forsyth. Radiant warmth and feeling flowed everywhere in this concert, starting from Richard Strauss’s lovely Sextet from Capriccio and ending with the energy and romantic ardour of Tchaikovsky’s late sextet ‘Souvenir de Florence’. In between was Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht , also painted in luxuriant colours, though here some sharper, more distilled contours might not have been out of place. It was a particular joy to see the Jerusalem Quartet in its fullest splendour: the Vancouver Recital Society sponsored the ensemble literally from its birth-pangs two decades ago.

As part of the Symphony Center Presents chamber music series, renowned husband and wife duo Pinchas Zukerman, viola, and Amanda Forsyth, cello, along with the acclaimed Jerusalem Quartet presented a program of lush, fully developed works at Symphony Center, 220 S. Michigan Avenue, Chicago on October 7, 2018.

This probably shouldn’t be taken as an invitation to behave badly at a classical music concert. But Amanda Forsyth says she wouldn’t mind it if you behaved badly at a classical music concert.

“I think they should do what they want,” says the cellist, on the line from her home in New York City. “The whole problem with classical music is that everyone thinks they have to behave. What has to happen is the music fills their bodies and makes them feel something, whatever it is they want to feel.”

In the crowded dressing room that she and Pinchas Zukerman share backstage, Amanda Forsyth was tidying up the pieces of her last solo concert as a member of the National Arts Centre Orchestra.

It was a night of significance for the institution and for the principal cellist of NACO, who will leave the ensemble at the end of this season.

Forsyth has been a “presence” with NACO for 17 years. Call it star power or charisma, when she is on stage people watch her.

Thursday night she gave them something more to look at and, in an interview later, to think about.

Hannah Nepil speaks to Amanda Forsyth, lead cellist of Canada’s National Arts Centre Orchestra, ahead of their collaboration with the RPO at the end of the month.

There’s a matter-of-fact quality to Amanda Forsyth’s voice when she says, ‘it was the worst and best time of my life.’ The Canadian cellist is describing the run-up to the 2011 world premiere of A Ballad of Canada, the last piece ever composed by her father, Malcolm Forsyth. He was suffering from pancreatic cancer at the time and had been told he had two months to live. ‘But he lived for nine and the reason was that he had this premiere and he wanted to be there. And he was. Somehow he managed to get, with his oxygen tanks, to Ottawa,’ Forsyth recalls.

Don’t tell Pinchas Zukerman, but Amanda Forsyth has another man in her life. His name is Carlo. He’s Italian, 300 years old, about four feet tall and made of wood. On second thought, Zukerman has probably met this guy. He lives in a special carbon fibre case in the home he shares with Forsyth. Carlo is, after all, a cello and a very expensive one at that, having been made by Carlo Giuseppe Testore in 1699 and being worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. That all makes Forsyth pretty protective of old Carlo, her nickname for her instrument.

“He’s my other husband,” she says. “Whenever I go to Italy, I always open his case and say welcome home.”

As quick to laugh as she is quick to judge, mostly herself, Amanda Forsyth is a dedicated musician, creative artist, stylish beauty, and engaging personality.

Born in South Africa, Forsyth came to Canada when she was very young with her father, composer Malcolm Forsyth, and her mother Lesley, a former ballet dancer. The University of Alberta, near where the family lived in Edmonton, offered a Suzuki music program in cello and so, at the tender age of three, she was enrolled to begin her musical training and take her first steps towards what has already been an impressive career.

“As a kid, music was just something to do initially but my parents saw hints of talent, even at that age, so they encouraged me in that direction. And I was a bit of a stage bunny so I loved the performing aspect. I was a typical kid so I didn’t always want to practice but luckily had enough natural talent to make it seem I had.”

Looking every bit the Greek goddess with her golden hair and the Mediterranean brightness of her flowing sapphire blue gown, Canadian cellist Amanda Forsyth played Electra Rising at the final concert of Symphony Nova Scotia’s current season in the Cohn on Tuesday night.

No one knows this work better than Forsyth, and not just because it leapt out of her own gene pool, having been written for her by her father Malcolm Forsyth. But she has performed it so many times it flows out of her fingers and her bow as if it had a voice of its own.

The basic gesture of the music is a flowing melody broken up by agitated scrubbings on the lower strings and played against a feather light accompaniment of tiny music from strings, woodwinds and harp.

A couple of years ago, the organizers of the Outaouais Festival of Sacred Music decided to offer concerts in Ottawa as well as in what we now call Gatineau. This was probably a good idea since the few suitable venues north of the river are difficult to find if you don’t know the city well. Then there was the problem that the best and most relatively findable performance space, the St-Benoît-Abbé church, became unavailable. (It’s soon to be converted to a palliative care facility.)

So this year’s festival opened at Southminster United Church, about a block from the Mayfair Theatre. How was the Friday night parking? You don’t want to know. The program featured cellist Amanda Forsyth and friends and was made up of two works, Ravel’s Trio in A minor and Messiaen’s Quatuour pour la fin du temps (Quartet for the End of Time).

What with her out-on-a-limb fashion sense, her romance with conductor-boss Pinchas Zukerman, and her kick-ass karate chops, drop-dead blonde Amanda Forsyth is not your standard classical musician.

On stage, she stands out. Like a radiant in a dark orchestral sea, Amanda Forsyth glows in the front row of the National Arts Centre Orchestra. Her hand flutters around the neck of her cello; her body sways ever so slightly, moved by the power of the music. At moments, a smile flickers across her face, reflecting the sheer thrill of making such a beautiful sound. With a growing solo career and a 1997 Juno Award, Forsyth is ranked by reviewers as one of the best Canadian cellists of her generation.

What’s more, she’s gorgeous.

![Zubin Mehta & Israel Philharmonic – The Mumbai Concerts – with Forsyth, Matsuev, Zukerman [Accentus; DVD]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bb977a8e5f7d14af77ae9d1/1567894689869-F41N4175OP0X1I9XVR0W/DVD.png)